On Sundays at 10 a.m., this alleyway in West Babylon, New York, fills with the sounds of cooing and clucking, wings beating against chicken wire, and the guffaws and grumblings of a group of longtime friends and foes.

Across the street, alongside the chain-link fence abutting Wellwood Jewish Cemetery, doors of pickup trucks bang shut as men carrying slatted wooden boxes stride toward the alley. On their car windows, alongside Mets bumper stickers, you might spot a subtle pigeon decal. A few stray feathers drift across the asphalt.

If you are a pigeon fancier—also known a mumblers or a flier—from the New York metro area, the auction at E. F. Pigeon is the place to be on a Sunday morning. As the bidding gets organized inside a warehouse space off the alley, the fliers gather around an outdoor coop in the parking lot for coffee and a smoke. There are shoulder claps, gibes, and side-eyes as friends and competitors arrive. The pigeons mill about in their cages, murmuring and churring like the men.Inside, the smooth, rolling calls of auctioneer George Ruotolo begin to echo off the metal ceiling and carry out to the lot: "Ten bucks apiece, ten dollars once, ten dollars twice!" Ruotolo, who is a hair stylist in his other incarnation, sports a smooth comb-back and a camo shirt, and has a thick Long Island accent. He perches on a crate above a stack of cages filled with birds.

About twenty men and a couple of women—almost all middle-aged and of varied racial backgrounds—are gathered before him, eyes fixed on the birds in his hands.

Almost everyone is wearing a mask, but there's no social distancing going on here: you have to get close to see the birds, which come in myriad colors and lustrous plumages. These are not street pigeons: they are immaculately groomed and cared for. Most of the fliers know one another and their pigeon proclivities, but if you're a newcomer, the first question is "What's your breed?"

The warehouse is outfitted with stacks of pigeon feed bags and an assortment of office chairs, where the fliers perch to trade notes and gossip. At the front, a woman sells coffee and alfajores cookies next to a display of miniature roosters, also for sale, whose insistent cockadoodledoos occasionally drown out the auctioneer."Sold!" he shouts. "Here ya go, pal." Cash and birds are exchanged across the tops of the cages. The birds appear calm and alert in their new owners' hands.

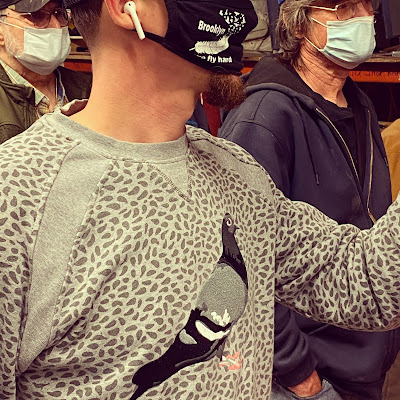

One guy, who is documenting each sale on his phone, wears a pigeon-themed sweatshirt and a mask printed with "Brooklyn We Fly Hard."

Over a stack of pigeon feed, two white-haired men in windbreakers gossip about a retirement community a friend has moved two. "Lotsa swingers down there, I hear. That's where I wanna go. I wanna get outta my house and swing!" But their attention is diverted by a trio of white birds that's creating a flurry of bids. "Fifty-five! Sixty-five! Ho!" The crowd yells: "Shit!" The auctioneer calls: "Eighty! Let's hear it!" "Ow!" the crowd responds. In their cages and boxes, the birds flutter, picking up on the excitement. The three birds sell for eighty-five dollars. Someone jeers, "He just got his retirement check!"

Behind the auction block is a separate room where the pigeons are bred. Pigeons mate for life, and each couple has its own cage, the male and female taking turns sitting on the eggs, which are nested in terra-cotta dishes.

The room smells like hay and seeds with an acidic undercurrent of pigeon guano. The pigeons cheep and cluck and preen and purr, filling the warm space with an attentive parental energy. The pigeons seem to be trading notes through the cage bars just like the fliers on the other side of the wall.

Though baby pigeons are a perpetual urban mystery, they're easy to find here, soon to be held aloft above a crowd and, after that, to swoop over Long Island lawns and Brooklyn rooftops.

Besides the lack of women in the crowd, there's a dearth of young people interested in pigeon racing. One man remarks: "The kids these days, they're all—" He bows his head and taps his thumbs on an imaginary smartphone. So the group is particularly excited by the arrival of a young pigeon enthusiast and his stuffed-animal pigeon. He is peppered with questions and advice: "What's your favorite breed?" "Where do you live—you say you got a rooftop?" "So you wanna race 'em?" "Gotta start the flock small, build from there." The stuffed pigeon soon finds itself hoisted above the crowd: "A hundred fifty for this pigeon!" Out in the lot, one man says to another: "You see everything at this auction."