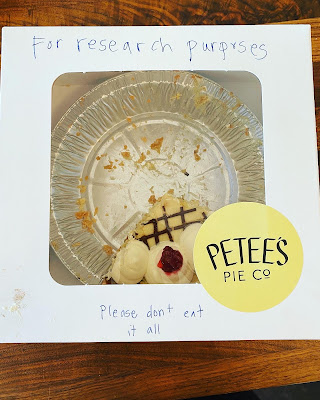

The pie is named after Count Karl Robert Nesselrode, a German diplomat who served as Russia's foreign minister and also happened to love chestnuts. He played various political roles across Europe during the reign of Napoleon, fighting his power at every turn, and died in St. Petersburg in 1862. Allegedly, his personal chef, Monsieur Mouy, created this pie for his boss after the signing of the Treaty of Paris, in 1856, which was not necessarily a victory for Nesselrode's political aims but marked the beginning of his retirement. As his eponymous pie soon would, Count Nesselrode faded into history.About a hundred years later, however, in the 1940s and '50s, the pie was mysteriously resurrected in a brownstone restaurant on Manhattan's Upper West Side. Hortense Spier delivered her Nesselrode pie to high-end restaurants across the city, particularly around Christmastime. Bakeries—including Mrs. Maxwell's, in East New York—attempted to re-create it, and newspapers and magazines printed variations on the recipe, with and without a crust, for ambitious home cooks. The signature ingredients were chestnut puree, rum or brandy, whipped cream, chocolate shavings, and candied red-and-green fruits for Yuletide. After the Spier family stopped baking it, the pie faded into oblivion—until Petra and Robert Paredez decided to try their hands at a Nesselrode at their shop, Petee's Pie Company, on the Lower East Side and in Clinton Hill.

A monthly blog about the sensory experience of New York City

Sunday, December 19, 2021

TASTE: Nesselrode pie, a long-lost New York City Christmas tradition

Tuesday, November 23, 2021

SIGHT: Mariners Marsh Park: the eeriest place in New York City

Just a few days after Halloween, I headed to Mariners Marsh Park, in the northwest corner of Staten Island, for a solo autumn leaf-peeping hike. I soon found myself in one of the eeriest and most beautiful places I've encountered in the five boroughs. The park comprises 107 acres of pin oak forest, ten ponds, and wetlands. But hidden among the trees and marsh grasses are ghostly remains of the factories once located on this land (and, according to the New York City Parks website, Lenape Indian artifacts). I couldn't help feeling like I was trespassing as I squeezed through a gate rigged to admit only the most determined of explorers.

The park has been closed to the public since 2006 for an environmental investigation. In the 1900s, the land was home to an ironworks and, later, a shipbuilding foundry. The ponds that now reflect the autumn sky were man-made and were used by both industries. Beneath their serene surfaces lurk hazardous chemical residues; a few backhoes and piles of sandbags on their shores indicated that the area is being remediated. But on the day I visited, the machinery was silent. Rusted rain tracks appeared from the underbrush, leading into a tangle of vines.

As I walked alongside the rails, I heard a ghostly whistle and clanging in the distance. Peering through a chain-link fence, I saw a modern freight train lurching past, spattered with graffiti spelling out "DO IT." The freight line of the Staten Island Railway skirts the southern end of the park, but this train seemed to be slicing through the wilderness.

In spots, the disused trail dissolved into a tunnel of vines; I had to duck to move forward, and despite the whine of the train, I felt impossibly far from humanity. If something happened to me, who would know?

There were signs of past visitors, however: rusted beer cans and even discarded clothing, seemingly belonging to a child.

Though there are official trails, the signs are sparse and faded. I trusted my innate sense of direction (Google Maps was not much help), following vague turns, until I stumbled upon concrete mounds rising out of the leaf litter like the remains of a fortress from an ancient civilization.

One section of wall had windows looking out on the underbrush.

A section of brick wall lay atop the fallen leaves as if dropped from above.

I bushwhacked through tall grasses, mud squelching underfoot, trying to recover the trail. After ten minutes of guessing which turns to take, Monument Pond appeared through the rushes, a serene pool reflecting the sky and treetops.

On the shore were more ruins.

Friday, October 22, 2021

Rice pudding—that humble, homely, nourishing dessert—has been an unsung staple of New York City cuisine for centuries, brought here in many varieties by waves of immigrants from around the world. The European version can be found everywhere from traditional Jewish and German delis to Delmonico's, and countless varieties are served at Asian, Middle Eastern, North African, Latin American, Caribbean, and South American restaurants. All usually include rice, milk, and sugar. Rice pudding was a mainstay of my own diet as a new arrival to the city in my early twenties. Kozy Shack rice pudding, the ubiquitous and inexpensive grocery store brand, often served as my breakfast and midnight snack in the same day. Rice to Riches, a space-age NoLiTa shop that sells nothing but rice pudding in flavors from "Play It Again, Butter Pecan" to "Sex, Drugs, and Rocky Road," fed my friends after late nights spent bar-hopping along Spring Street.

As it turns out, Kozy Shack rice pudding was born in New York City at a deli called the Cozy Shack on Brooklyn's Seneca Avenue. The deli was known for its homemade, kettle-cooked rice pudding as well as for its sandwiches, and a deliveryman named Vinnie Gruppuso became such a fan of the pudding that in 1967 he decided to buy the rights to the recipe and rebranded the deli's name for the package. With the help of his friend Sam Walton, founder of Sam's Club and other big-box stores, Kozy Shack made its way onto grocery store shelves and into home fridges across the country. One of the things that drew me to Kozy Shack as a twentysomething was its surprisingly simple list of ingredients for a mass-produced product: milk, eggs, rice, and sugar, which remains the recipe today.

The rice pudding that fed German immigrants in the nineteenth century wasn't too different from Kozy Shack's, so I decided to find the most traditional version still made here today. I headed to Glendale, Queens, to Stammitsch Pork Store, one of the city's last remaining German delis, in a Tudor storefront with heart-shaped cutouts in the shutters and mums in the windowboxes.

The firm, nutty grains of rice broke into the faintly sweet, eggy, creamy base, spiked by the occasional sour, dry shock of cinnamon.

I'm sure many new immigrants to New York would raise an eyebrow at the idea of a path from "rice to riches," but the sticky, glutinous sound of a spoon sinking into the pudding and the first taste of blandly sweet custard brought me back to my early, innocent, hungry days in the city and the comfort of a simple, healthy, rib-sticking dessert.Monday, September 20, 2021

SMELL: The fragrance of One World Observatory

The perfume's citrus notes intensify as you proceed down a screen-lined hallway and stifle any damp, mineral-y smell one might expect in a tunnel carved through the actual bedrock supporting the 104-story tower.

A man with a selfie stick extended his arm like an archer poised for a shot as a couple of backpacked women rummaged through brochures. All were within inches of the scent diffusers, but did they notice in the lofty air an essence of roots, of bark, of history? Dani, a "tour ambassador" in a red vest, pressed her lips closed when I asked her about the scent. “We’re not allowed to talk about it.”

Sunday, August 22, 2021

SOUND: Macy's wooden escalators

Your hopes rise when you glimpse the handsome wooden escalator bank, hewn from original oak and ash in the 1920s and '30s, when the moving stairs were constructed by the Otis Escalator Company. But you soon find that the treads are made of aluminum and utter hardly more than a mechanical purr.